COURSE TITLE: “Shakespeare in Medicine.”

CODIFICATION:

NUMBER OF CREDITS/HOURS: 3 credits/ 72 hours

NAME OF COORDINATORS: Angel A. Roman-Franco MD

COORDINATOR’S OFFICE: Department of Pathology; A359

COORDINATOR OFFICE AND CONTACT PHONES: 758-2525, ext 1526

MEETING PLACE: Dept. of Pathology meeting room

HOSPITALS: None

PRE-REQUISITES: None

CO-REQUISITES: None

“Dying is not romantic, and death is not a game which

will soon be over…Death is not anything…death is not

…It’s the absence of presence, nothing more

…the endless time of never coming back

…a gap you can’t see,

and when the wind blows through it,

it makes no sound…”

“Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead”

Tom Stoppard

“Shakespeare is hard, but so is life.”

Fintan O’Toole

Shakespeare’s numerous forays into medicine, not unexpected being life so precarious in his time,[1] led him to allude to specific physicians as well as to numerous aspects of medicine as expressed in his character’s strengths and failings. Dr. William Butts, the real-life physician to Henry VIII takes part in the homonymous play. Helena, in All’s Well That Ends Well was daughter to Gerard de Narbon who shall be the object of latter reference. Coeval with the publishing of Andrea Vesalius’ Fabrica, (vide infra) Shakespeare’s plays abounds with allusions to the nature of the human body — its birth, maturing and inevitable death. Gloucester in Henry VI describes his birth: “For I have often heard my mother say, I came into this world with feet forward.”

Richard III complains that he was,

Deformed, unfinish’d, sent before my time

Into this breathing world scarce half made up,

A phrase contrasting powerfully with King Hamlet ghost’s evident reversal of fortune:

Thus was I, sleeping, by a brother’s hand,

Of life, of crown, of queen, at once dispatch’d:

Cut off even in the blossoms of my sin,

Unhous’led, disappointed, unanel’d;

No reckoning made, but sent to my account

With all my imperfections on my head

The doctors in Shakespeare’s time held that wounds should be protected from air, thus

The air hath got into my deadly wounds,

and much effuse of blood doth make me faint.

as the patient goes into hypovolemic shock. He clearly understood the connection of mind and body when he has King Lear’s clamor:

… this tempest in my mind

Doth from my senses take all feeling else.

Falstaff speaks of “inland petty spirits” in his monologue on the advantages of alcohol in Henry IV Part2; King Lear exclaims “hysterica passio…down, thou climbing sorrow.”[2] What were the associations evoked amongst the public by Parolles’ reference to the art of “both of Galen and Parcelsus[3]” when All’s Well That Ends Well was first staged around 1604?[4] And what would have been the audience’s reaction to having a woman cure the French king’s fistula when women were not even allowed on stage?[5] Close to 800 medical allusions are found in William Shakespeare’s plays and poems. The emotional and physical predicaments of his characters are part and parcel of the logic inherent to his plays, with health, illness and cures providing metaphors, as in Plato’s Dialogues[6], to shed light upon more profound situations.

Clearly the technical aspects of medicine have undergone vast changes since the Elizabethan Age. But it’s a doubtless assertion that the humanistic contours remain virtually unchanged, for Shakespeare’s dramatic representation of illness and its effects are not only as pertinent then as they are today: they are some of the most paradigmatic delineations of human psychology and psychopathology in all of literature. In short, Shakespeare is a far better analyst of the human circumstance than any psychiatrist or psychologist before or since. Harold Bloom has credited Shakespeare with the very invention of the modern mind, through characters like Othello, King Lear, Macbeth[7], and Hamlet: a position I dare not challenge. Only the greatest among the great, viz., Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Tirso de Molina, Mozart and Goethe can claim to have scaled such lofty heights of insight into the psyche on a stage: the same unassailable feat achieved by Cervantes with his realistic and nuanced foundational characters: Don Quijote and Sancho Panza: insights into the human psyche that with Shakespeare’s presage our understanding of the mind.

Shakespeare’s blazing perceptiveness of man’s achievements as well as his foibles, together with his archaic style as well as the evocative power of his logos bring not only depth, breadth and heightened scope, but unique freshness and charm to our continued contemplation of the art of medicine. It is for this particular reason I have chosen, as tools for fostering the appreciation by students for the role of high drama in shedding light on the human condition, the four major tragedies wrought from the pen of William Shakespeare: Hamlet, Othello, King Lear and Macbeth. Given the fact that as physicians they will be dealing not merely with organic disease, but with disease within the context of each and every individual’s predicament, such as a person’s reaction to disease and hence to the precariousness of life, Shakespeare illumines that condition like few, if any, with his searing intellectual searchlight. And his reach is vast: from Hamlet and the ambivalence of youth, to the harrowing descent into decrepitude of Lear.

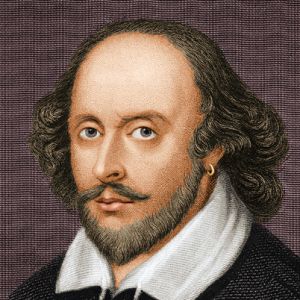

The year 1564 is truly an anuus mirabilis. That year saw the birth of William Shakespeare, but in addition saw also the birth of Christopher Marlowe and that of Galileo Galilei, -born three days before Michelangelo’s death (incidentally, Galileo was a physician having obtained his degree at the University of Pisa) -a passing of the palm of learning from the fine arts to science. The year of Galileo’s death -1642- saw the birth of Isaac Newton. The year of Shakespeare’s birth also saw the passing away of the premier anatomist Andreas Vesalius (another physician, graduate from the University of Paris; class of 1537). Galileo’s epochal Sidereus Nuncius, where he describes his observations of the distant heavens, was the equivalent of Shakespeare’s inimitable exploration of the innermost depths of the human psyche and with it the re-invention of classical Greek drama.

Shakespeare is doubtless a child of the late 16th and early 17th century and thus of the English Renaissance, and flourished amidst the glories of the times. Born at the dawn of the post-reformation period, the beginning of which is attached to the death of John Calvin (1564), he died on 1616 at age 52 after writing 38 plays, 148 sonnets and several lengthy poems. During his lifetime he saw published Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius (1609) and Cervantes’ Don Quijote, but his untimely death deprived him of reading a salient contemporary’s magnum opus: William Harvey’s Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (1628) which chronicles his discovery of the circulation of the blood. In 1589 Shakespeare wrote his first play: A Comedy of Errors. King Lear, Macbeth, Othello and Hamlet were some years in the future and The Tempest marked his exeunt. It is nigh short of miraculous: the conjunction of some of the greatest minds the world has known: Tirso de Molina, Galileo, Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, Rene Descartes, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir William Spencer, Sir Francis Bacon and William Harvey, are coeval with Shakespeare, as was Baruch Spinoza, the only person known to have the honor of having been excommunicated by two religions: Judaism and Christianism. And how could one fail to highlight the fact that Western Civilization lost two of its greatest foundational luminaries in the year 1616: Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra and William Shakespeare: both died on St. George’s day: contemporaries in life as well as death. Hamlet brooded over his uncertainty; Calderon’s Segismundo would soon brood, like Hamlet, over the vapidness of the world whilst Cervantes’ “Knight of the Woeful Countenance” countered by creating his own very personal panoramic universe: “Demasiada cordura puede ser la peor de la locura, ver la vida como es y no como debería de ser.

I lay such importance on Cervantes vis-à-vis Shakespeare because England, in the judgment of the French historian Roger de Manvel, “Has held Cervantes to her heart as though he were her very own son. Don Quixote is certainly an un-Spanish book in many ways.”[8] Just like Shakespeare’s characters, Don Quijote has reached mythical proportions. It is useful to remember that the mythification of Don Quijote’s persona is accomplished by the combined assessment of Galdós[9], Valera,[10] Pereda,[11] Ganivet,[12] Maeztu,[13] Ramón y Cajal,[14] Macías Picabea,[15] Valentín Almirall,[16] Mallada,[17] Silió,[18] and others. When Don Quijote reaches Miguel de Unamuno he has already been mythified.[19] But not just Don Quijote: Sancho Panza too has grown mythic in size to become far more than the knight’s squire. His comic wisdom is matched only by that of Shakespeare’s Falstaff’s or that of the Fool in King Lear. Sancho knows that Don Quixote spells trouble and in dealing with it he is the peer of Lear’s Fool.

Like Cervantes, Shakespeare was very much a child of his age. The latter’s medical allusions can be traced to the medical knowledge of his times, when Elizabethan medicine was still under the paradigm of the four humors of Aristotle. Derived from liquor, the original Latin meaning of the word, which signified “liquid,” the humors were deemed the rulers of our passions. In the 1600’s physicians understood the four humors to signify patterns of speech, behavior and other qualities that predominate in a human being. The four primary humors are blood, phlegm, choler (yellow bile) and melancholy (black bile), which are presumed to dominate a person’s temperament. References to humors as a variety of human temperaments appear prominently in Shakespeare’s plays. It should be noted that the Hot-Cold theory of disease based on equilibrium of the four humors is very much present amidst Puerto Ricans and is certainly part of the medical lore of the older generations.[20] The humoral medical paradigm, descended from Hippocratic medicine and through the Arabs made a part of Spanish medicine, has been reported in all mainland Spanish-American countries and not just Puerto Rico: Brazil, Haiti, amongst Puerto Ricans in New York City, the American southwest, Trinidad and Tobago and the Philippines.[21] Among the characteristics that singly or in combination have been used in different cultural contexts, for the theory is nigh as universal as it is binary, to classify food and to direct food intake are: hot-cold, wet-dry, male-female, heavy-light, yin-yang, pure-impure, clean-poison, and ripe-unripe. “Flavor,” “sharpness,” “itchiness,” and “color” are additional terms, less frequently encountered (Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1968[22]; Ahern, 1975[23]; Colson, 1976[24]; Beck, 1969[25]; Messer, 1981[26]). One can only marvel at the fact that these perceptions, born with Hippocratic medicine, have held hold to this day: the better of two and a half millennia.

The Hippocratic humoral theory of disease remains one of the most important and often misunderstood concepts in the Hippocratic Corpus.[27] It is a theory that has been the subject of much undeserved criticism by some of today’s medical historians and physicians: arrogance nurtured by ignorance. This medical system, when viewed in its most minute local details, conforms to a comprehensive theory whose most noticeable characteristics are simplicity and uniformity, from one community to the next, from one country to the next, from one continent to the next. (ref. 21) One can say that it is Euclidean in scope. In coming to a proper understanding of its significance as it is employed by Elizabethan physicians as well as Shakespeare, it is important to highlight that with this doctrine the Greeks for the first time in history confronted us with direct observation of disease processes without recourse to magic. Those, and a natural metaphysics developing in Ionian Greece, are blended enabling physicians since to formulate a rational and naturalistic theory of disease. Prior to this time it was all shamanism.[28]

Anaximander of Miletus (c. 610-510 BCE) and Thales of Miletus, (620-546 BCE) were the first philosophers to resort to direct first-hand observation of reality and logical argumentation and thus develop a rational conception of existence. Anaximander’s theories about the nature of reality centered on the idea of opposites with existence representing a type of balance between opposing forces: certainly the initial underpinning for the hot-cold theory. Later thinkers re-formulated Anaximander’s theory of opposites into four properties: hot, cold, moist and dry. Empedocles of Agrigentum (fl. 450 BCE), like Anaximander and Thales was also of the school that tended towards observation and logical argumentation. Empedocles linked the four opposing powers of hot, cold, moist and dry with four elemental components of existence: fire, air, water and earth. In the Hippocratic Treatise Ancient Medicine (written c. 400 BCE) these are subsumed into the four classical bodily fluids: phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile. Disease, in essence, becomes a state in which one of these four bodily fluids (humors) overpowers the others. Galen of Pergamon’s (129-200 CE) writings included the works of Hippocrates and of two other leading Alexandrian physicians, Erasistratus of Chios[29] and Herophilus of Chalcedonia.[30] His works comprehensively rationalized and systematized ancient Greek medicinal knowledge and exercised authority for over fourteen centuries, much like Ptolemy. By Elizabethan times, errors had been pointed out in Galen’s work and there was growing skepticism towards his theory and method. However, Galen’s basic assumptions persisted widely –all the way up to recent Puerto Rico-, and Shakespeare makes frequent use of traditional Galenic notions and utilizes his audience’s familiarity with them, as in the following example:

- Pedro: Sigh for the tooth-ache?

Leon: Where is but a humour of a worm? Through all thy veins shall run

A cold and drowsy humour.

This is undation of mistemper’d humour

Rests by you only to be qualified;

Then pause not; for the present time’s so sick,

That present medicine must be minister’d.

These lines from Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing give a brief glimpse into the world of Elizabethan medicine as inspired by Greek medicine and extending all the way to 21st century Puerto Rico. Indeed an understanding of these concepts is essential for the proper study and analysis of Puerto Rican medicine and pharmaceutical sciences up to the 21st century. Thus it is not surprising that in Latin American culture it is believed that hot foods are more easily digested than cold foods. Being it that the stomach therefore it is believed that all food must become warm in the body before it can be digested.[31]

Andreas Laurentius Mariscalcus (1558-1609) notable for his trenchant and acerbic remarks (e.g.,: “Cavemen understood grammar better than some Latin teachers…”), Professor of Medicine at Montpellier and a most distinguished physician of the Elizabethan period summarized the topic thus:

…there are four humours in our bodies, Blood, Phlegme, Choler and Melancholie; and that all these are to be found at all times in every age, and at all seasons to be mixed and mingled together within the veins, though not alike for everyone: for even as it is not possible to finde the partie in whom the foure elements are equally mixed…there is alwaies someone which doth over rule the rest and of it is the partie’s complexion named: if blood doe abound, we call such a complexion, sanguine; if phlegme, phlegmatic; if choler, cholerike; and if melancholie, melancholike.[32]

Needless to say the milieu of the 16th century conditioned the beliefs, practices, and medical problems of its time as much as the same do ours. Even though based on a theory of humors, the human predicament this theory was attempting to address has changed very little since then: the zeitgeist of the sixteenth century with its angst and gestalt was but mildly different from today’s. Of course it was then believed that the aforementioned humors or fluids were a mélange; part and parcel of the body’s composition: to wit, blood, phlegm, choler (or yellow bile), and melancholy (or black bile). It was theorized that the predominance of one humor over the others determined a person’s temperament, be it sanguine, phlegmatic, choleric, or melancholic and any excess of any of them would underlie disease, thus the cure lay in purging or avoiding the peccant[33] humor, as by reducing the amount of blood by cupping[34] or reducing the bile by means of drugs. In Elizabethan times medicine remained mostly medieval; Aristotle and Hippocrates still cast a very long shadow though to it had become affixed lore and beliefs of a non-naturalistic tenor. Widely accepted during the medieval period, the medieval Hippocratic-Aristotelian school of thought saw the medieval accretions of magic and astrology significantly diminished in Elizabethan times. Yet, some physicians still believed that if the planets were improperly aligned, an individual would get sick or die, according to astrological portents. Thus Calpurnia’s warning to Caesar, and his formidable riposte:

And the seer’s warning to Caesar which foretells his death:[35]

Which later is reaffirmed:

Aside from astrological portents, Elizabethan physicians as well as the public also believed that certain gemstones held medicinal powers. Garnets were believed to keep sorrow at bay. For treatment of choler or anger topaz and jacinth were used, whereas emeralds and sapphires were thought to bring tranquility to the mind. This is not too far from the present use of magnets, and the emergence of such grotesquerie as the “Magnetic Field Deficiency Syndrome” amongst naturopaths[36], this despite their pompous motto: Vis Mediatrix Naturae, lifted from Hippocrates.

Given the rise in urban populations during the renaissance, epidemic diseases increased in frequency in the sixteenth century. Salient were typhus, smallpox, diphtheria and measles. Scurvy also became more common whereas leprosy became rather rare. Epidemic childhood diseases abounded, such as plague, measles, smallpox, scarlet fever, chicken pox, and diphtheria. Many children were thus abandoned, especially infants with syphilis (it was feared they would pass it on). This gives meaning in King Lear to the Duke of Kent’s terrible curse he places on Oswald:

“A plague on your epileptic visage!” King Lear, II, 2, 81

Here Kent employs the word ‘epileptic’ in reference to the pock-marks of syphilis, endemic in Elizabethan England, and is not actually a reference to epilepsy itself. In the sixteenth century syphilis continued to be common and the favored treatment was with mercury or guaiac. Gonorrhea became even more common. These two venereal diseases were directly responsible for the closing of communal baths, which were the only convenient means of personal hygiene. This eventually had an impact on the hygiene of chimney sweeps and thus their propensity to scrotal cancer.[37]

Elizabethan medical treatments were quite varied and some decidedly effective. The first successful remedy for ague (malaria) was a plant derivative from Peru called cinchona.[38] It cured quickly and acted specifically on only a certain kind of fever. Exploitation of the cinchona bark, first discovered in Peru, began in the 17th century by the Jesuits. The history of the discovery of its curative effects is not clear but the first recorded shipments of the bark to Rome were in 1631, 1632 and again in 1645.

In 1645 Father Bartolomé Tafur contacted Cardinal Juan de Lugo to present him the miraculous Peruvian bark. The Cardinal subsequently had the bark tested by Gabriele Fonseca; physician to Pope Innocent X[39]. Fonseca found the cinchona bark to be a very salutary medicine. Doctors and Jesuits returning from Perú were soon encouraging the rapid spread of the use of the cinchona bark against fevers in Italy and in Spain.

Meanwhile in England there was a lot of resistance to the use of the cinchona bark due to the bark’s association with the Jesuits.[40] Oliver Cromwell could have escaped death from malaria had his physicians used the “popish powder”[41] during the course of his treatment. With the specificity of cinchona the belief in fever as a general manifestation of unbalanced humors was dealt a severe blow. It was then felt that each fever could be a different disease. For an earache, a common remedy was to put a roasted onion in the ear.[42] The tail of a black cat was believed to cure a sty if stroked over the afflicted eye. To achieve the salutary effect the person was supposed to rub his eye with the cat’s tail. Captain Cook ameliorated the scourge of scurvy amongst his sailors healthy from scurvy by giving them lemon juice, a source of ascorbic acid, together with ale.[43] For mental illness, Jean-Baptiste Denis[44] extended the new technique of transfusing blood to the treatment of mental patients. When arterial blood of lambs was injected into the venous system, the patients seemed to recover. This method was stopped when a patient died. This mélange began to be somewhat more rationally organized with the arrival of the renaissance and its recovery of the classical outlook.

The physicians of the Elizabethan period, however, were men of good education. Their degrees were generally taken abroad and were then incorporated at Oxford or Cambridge. A very thorough examination had to be passed before licenses were granted for practicing in the metropolitan area.[45] The college was less severe about licenses to practice in the country. Elizabethan medicine was very different from our present day practices and beliefs as were the medical problems of the 16th century. Elizabethan medicine was not very advanced, with old beliefs overshadowing the knowledge of new discoveries about the human body. However, the medical profession advanced through the establishment of standards and a common board by which the public could benefit: a prelude to our present “best practice guidelines”(ref.33). Thus we must view Shakespeare’s medical allusions within the historical moment in which he lived.

What theories and discourse prevailed regarding human nature suffered a unique transformation during Shakespeare’s productive life in Elizabethan England. The meaning and foundation of the psyche, as well as those of the soma, achieved primacy and retained their presence as cardinal elements in humanistic thought. Previously mankind had been regarded as intrinsically insignificant, save for its relationship to God, and this doctrine extended up to the Elizabethan society. The Renaissance brought man to hitherto unparalleled predominance: a dramatic drift away from the prevailing societal, religious and philosophical tenets as centers of attention that led to an unprecedented focusing on man and his environment, as opposed to God’s. Man surfaces again, since classical antiquity, [46]as a premiere subject of inquiry, thus Shakespeare’s turning of his searching intellect onto the travails of human existence: it was the avant-garde topic of his time. Elizabethan philosophers and physicians were never able to fully shed the psyche-soma dyad. The rift between the two became possible because of the profound scientific changes that occurred during the Age of Reason, by which time the glimpse of a cleavage in the Elizabethan soul became a chasm, and made possible the secular study of man’s physical and rational attributes. In no small degree this was propitiated by Descartes’ oeuvre.[47] And this cleavage marks the beginning of the decline of Aristotle’s concept of sensus communis.[48]

Prior to the renaissance and beyond, physicians frequently treated the human being—body, soul, and ‘spirits’—as a single entity, resulting in a holistic approach (hence the sensus communis). But at the renaissance’s outset doctors soon began to dissect the body, both figuratively and literally (recall Vesalius), and sought to consider each new part independently. This materialist reductionist approach is a recovery of the Ionian scientifico-philosophical method as exemplified, for example by the Ionian Xenophanes of Colophon (570-480 BCE) who devastated the Homeric gods with scorn thus: “If they could paint, he says, ‘horses would paint the forms of the gods like horses, and cattle like cattle’; for ‘the Ethiopians say their gods are snub-nosed and black, the Thracians that they have light blue eyes and red hair.’ Men have made their own image into gods. All these things are ‘fictions of the earlier people’ which should not be repeated”[49]

Again the soul became neglected, but not entirely disregarded. Despite the persistence of the soul’s importance, conflict between spiritual and scientific leaders of the day resurged when experimental science, introduced by Francis Bacon, began. An approach greatly strengthened by Galileo’s mathematico-experimental approach. Clergy and physicians often gave contrasting advice thus undermining each other. However, the predominant paradigm of Elizabethan society was that the ideal condition of man was that of a “sound mind in a sound body”[50]—any outside influences on a human being would eventually have both spiritual and physical ramifications.

Thus we have briefly touched upon the meanderings of medical and psychological topics addressed through the ages. It is notable, as we have already mentioned that even contemporary Puerto Ricans still hold in abeyance the humoral theory and, particularly among the elderly, bring it to the fore to explain their symptoms, be they organic or mental. This trait brings them into confluence with some of Shakespeare’s thought, particularly as it pertains to the behavioral. Therefore we have selected for this course the tragedies[51] of Hamlet, King Lear, Othello and Macbeth. Issues of death and dying, dementia, epilepsy, psychosis, depression, family relationships, father-daughter relationship, filial abuse, grief, history of medicine, homicide, incest, love and jealousy, mental illness, hallucinations, mother-son relationship, mourning, power relations, religion, sexuality and suicide are some of the medical and ethical issues brought to the fore by Shakespeare in these four great tragedies. Today they are paramount issues in our society’s pathology, thus worthy of our student’s attention, since ancient medical traditions color the way they are perceived and understood by a significant number of people. In Puerto Rico, medical traditions of yore still condition a patient’s compliance with therapy, diet and disease prevention as well as behavior both social and familial. What better approach to these subjects than through these four formidable pillars of Western Civilization.

THE PLAYS

It is a grand and terrible thing that the hero should be the only one to see his heroism from the inside, to see into its very vitals, and that everyone else sees it only from the outside, in its external features. It is for this reason that the hero lives alone in the midst of men and that his solitude serves him as comforting company….he will be ready to bear with resignation the misfortune of having his neighbors judge him according to the general law and not the law of God.

Vida de Don Quijote Y Sancho

Miguel de Unamuno

MACBETH

KEY ISSUES: Death and Dying, Grief, History of Medicine, Homicide, Human Worth, Marital Discord, Mental Illness, Hallucinations, Nature, Obsession, Power Relations, Rebellion, Religion, Society, Suicide, War and Medicine, Women in Medicine and the role of the supernatural in the decision making process of individuals: a clear form of delusion.

“Strange things I have in head, that will to hand;

Which must be acted ere they may be scann’d”[52]

So says Macbeth after having experienced the hallucination of Banquo’s ghost: a form of premonitory vengeance. Some have looked at this scene through more benevolent and sanguine eyes. “Macbeth’s descent into madness often elicits psychological interpretations, but he experienced neurological and cognitive deterioration as well. This brings into question whether a psychiatric disorder alone could fully account for his condition. Any patient today, particularly one from Scotland, presenting with a similar rapid decline in neurological, psychiatric, and cognitive function, accompanied (as in Macbeth’s case) by involuntary movements, hallucinations, and insomnia, would require an evaluation for variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.”[53] This is sheer folly. A facile interpretation of the play could lead one to box the denouement and catastrophic finale in merely clinical terms. But Macbeth is far more than such. His awareness of his mental deterioration, his disdain of fate as well as for the inability of physicians to deal with “diseases” of the “mind” is expostulated, as this exchange about Lady Macbeth’s infirmity exemplifies:

MACBETH: Canst thou not minister to a mind diseas’d,

Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow,

Raze out the written troubles of the brain,

And with some sweet oblivious antidote

Cleanse the stuff’d bosom of that perilous stuff

Which weighs upon the heart?”

DOCTOR: Therein the patient

Must minister to himself.

MACBETH: Throw physic[54] to the dogs,

I’ll none of it![55]

In the scene where this question is asked, Macbeth is talking with Lady Macbeth’s doctor and asks if knowledge is available to help Lady Macbeth get over the trauma about which she is obsessing. No: Lady Macbeth is condemned to live with her merciless memories; for to recall our unchangeable and remorseless past is all there is to the human condition. We live in the present, but we relieve in our past.

Although Macbeth is Shakespeare’s bloodiest play, and it courses with dizzying rapidity conveying a deceiving sense of senseless, unremitting perdition, much better minds than mine have had other thoughts about the authors’ real purpose. For example, here is Nietzsche’s assessment as it appears in his Daybreak (sect. 204)

“Whoever thinks that Shakespeare’s theater has a moral effect, and that the sight of Macbeth irresistibly repels one from the evil of ambition, is in error: and he is again in error if he thinks Shakespeare himself felt as he feels. He who is really possessed by raging ambition beholds this its image with joy; and if the hero perishes by his passion this precisely is the sharpest spice in the hot draught of this joy. Can the poet have felt otherwise? How royally and not at all like a rogue, does this ambitious man pursues his course from the moment of his great crime! Only from then on does he exercise “demonic” attraction and excite similar natures to emulation—demonic means here: in defiance against life and advantage for the sake of a drive and idea. Do you suppose that Tristan and Isolde are preaching against adultery when they both perish by it? This would be to stand the poets on their head: they, and especially Shakespeare, are enamored of the passions as such and not least of their death-welcoming moods—those moods in which the heart adheres to life no more firmly than does a drop of water to a glass. It is not the guilt and its evil outcome they have at heart, Shakespeare as little as Sophocles (in Ajax, Philoctetes, Oedipus): as easy as it would have been in these instances to make guilt the lever of the drama, just as surely has this been avoided. The tragic poet has just as little desire to take sides against life with his image of life! He cries rather: “it is the stimulant of stimulants, this exciting, changing, dangerous, gloomy and often sun-drenched existence! It is an adventure to live—espouse what party in it you will; it will always retain this character!”— He speaks thus out of a restless, vigorous age which is half-drunk and stupefied by its excess of blood and energy—out of a wickeder age than ours is: which is why we need first to adjust and justify the goal of a Shakespearean drama, that is to say, not to understand it.”[56]

In a perversion of Nietzsche’s view, Puerto Rico nurtures more than our share of moral and ethically diminished persons in positions of power, thus our young men and women cling to the values these signify: to succeed at all cost in defiance of the Sophoclean maxim “better to fail with honor than succeed by fraud.” Clearly Macbeth a blazing incarnation of “the end justifies the means” – holds a mirror to us for us to foresee our impending disgrace. Macbeth in words that resonate as a metaphors through the entire play gives us his final truths – that once he has manipulated endlessly to force life itself to fit his self-made script, in the end, he has rendered his own life meaningless. Here we get a most profound statement of existential angst – without any moral code and in the absence of any higher moral authority –; he knows that like the rest of us, he will succumb to his own self-made fate:

I have lived long enough. My way of life

Is fallen into the sere, the yellow leaf

And that which should accompany old age,

As honour, love obedience, troops of friends,

I must not look to have, but in their stead

Curses, not loud but deep, mouth-honour, breath

Which the poor heart would fain deny and dare not. (5.3.23-29)

At the end Macbeth’s mind, despite its apparent resilience, caves in, and no better moment exemplifies this than the monologue in which he, after being informed of his wife’s death, broods:

“Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.”

Life abolished. The pacing cacophony preludes death.

These terrible lines call forth Pales-Matos’ formidable stanza;

Un mar hueco, sin peces,

agua vacía y negra

sin vena de fulgor que la penetre

ni pisada de brisa que la mueva.

Fondo inmóvil de sombra,

límite gris de piedra…

¡Oh soledad que a fuerza de andar sola

se siente de sí misma compañera!

OTHELLO

KEY ISSUES: , Domestic Violence, Grief, Homicide, Marital Discord, Obsession, Power Relations, Racial discrimination, Scapegoating, Suicide

Othello harbors perhaps the two most enigmatic characters in Shakespeare’s canon: Othello and Iago. The former has the more complicated personality. It may seem right to maintain that the Moor is intrinsically evil… no more than an “old black ram” (1.1.88), the historical icon of Satan. It is also quite plausible to claim that Othello has been infected with evil by his ensign, Iago, or even that Othello’s actions (e.g. the murder of Desdemona) were simply logical ramifications of what he can’t help but believe.[57] Burton offers an impeccable contemporary medical explanation for Othello’s precarious state of mind, attuned to Elizabethan times: “Most are of the opinion that it is the Braine: for being a kinde of Dotage, it cannot otherwise bee, but that the braine must be affected, as a similar part, be it by consent or essence, not in his Ventricles, or any obstructions in them, for then it would be an Apoplexie, or Epilepsie… but in a cold, dry distemperature of it in his substance, which is corrupt and become too cold, or too dry, or else too hot, as in madmen, and such are inclined to it.” (Burton, p. 163).

From the play it is evident Othello is an epileptic. Othello must, within the context of Elizabethan physiology, suffer from a lack of pituita, resulting in dryness and also of sanguine, or blood, resulting in coldness that would cause him to suffer such fits. Othello’s epileptic seizures would have other ramifications, as well, for, according to Burton, “our body is like a Clocke, if one wheele be amisse, all the rest are disordered, the whole Fabricke suffers…”(Burton, p. 164). This humoral imbalance would express itself as choler manifesting itself by severe bouts of anger, as evidenced by his plotting and actual murder of Desdemona and then his own destruction.

One cannot simply gloss over Iago. To see him merely as the incarnation of evil renders him trite and an unworthy assailant of Othello’s majestic figure. This archvillain is adorned by unplumbed amorality. Iago deceives, steals, and murders to gain the position he covets: Cassio’s. But unlike Macbeth, who is in a constant struggle with his own subsumed but evident morality, Iago, on the other hand need not concern himself with uncomfortable scruples: he lacks any. An ability to say the right thing at the critical time makes Iago not only villainous, but a satanic one at that. His amorality and cynicism make him the quintessential “Shakespeare’s villain.” No wonder William Robertson Turnbull has characterized him thus: “Iago is an unbeliever in, and denier of, all things spiritual, who only acknowledges God, like Satan, to defy him.”[58] Iago belongs to the tradition of satanic villains whose defiance is so powerfully revealed by Milton: Here we may reign secure; and in my choice

To reign is worth ambition, though in hell:

Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.[59]

In his barefaced love for evil Iago uses jealousy and anger as tools with which to perpetrate evil. Iago invents motives to provide the framework for his diabolical ploy. To Iago, Othello’s ruin is his ultimate objective. Thus Coleridge proposes the concept of motiveless malignity thus:

“The triumph! again, put money after the effect has been fully produced.–The last Speech, the motive-hunting of motiveless Malignity–how awful! In itself fiendish–while yet he was allowed to bear the divine image, too fiendish for his own steady View.–A being next to Devil–only not quite Devil–& this Shakespeare has attempted– executed–without disgust, without Scandal!—“[60]

Iago’s exploration of the most fetid depths of evil is what qualifies him as perhaps the most malevolent villain in all literature and none other than Giuseppe Verdi captures this in his extraordinary aria Credo in un Dio crudel (for which there is no direct paraphrase in the play, but more than enough conceptual justification).

Arrigo Boito’s Credo in un Dio crudel, Iago’s aria from Verdi’s Otello Credo in un Dio crudel I believe in a cruel Godche m’ha creato simile a sè who has created in His imagee che nell’ira io nomo. and whom, in hate, I name.Dalla viltà d’un germe From some vile seedo d’un atomo vile son nato. or base atom I am born.Son scellerato perchè son uomo; I am evil because I am a man;e sento il fango originario in me. and I feel the primeval slime.Sì! Questa è la mia fè! Yes! This is my testimony!Credo con fermo cuor, I believe with a firm heart,siccome crede la vedovella al tempio, as does the young widow at the altar,che il mal ch’io penso that whatever evil I thinke che da me procede, or that whatever comes from meper il mio destino adempio. was decreed for me by fate.Credo che il guisto I believe that the honest manè un istrion beffardo, is but a poor actor,e nel viso e nel cuor, both in face and heart,che tutto è in lui bugiardo: that everything in him is a lie:lagrima, bacio, sguardo, tears, kisses, looks,sacrificio ed onor. sacrifices, and honor.E credo l’uom gioco And I believe man to be the sportd’iniqua sorte of an unjust Fate,dal germe della culla from the germ of the cradleal verme dell’avel. to the worm of the grave.Vien dopo tanta irrision la Morte. After all this mockery comes death.E poi? E poi? And then? And then?La Morte è il Nulla. Death is Nothingness.È vecchia fola il Ciel! Heaven is an old wives’ tale![61]

Can any sentence more succinctly posit the whole of Iago’ purposelessness than “La Morte è il Nulla”

Does Iago displace Othello as the dominant character? Of course not! Iago is a one dimensional villain in the single-mindedness of his destructive purpose: and malignity is unidirectional and bereft of nuance: Iago is no Machiavelli. Othello doubts, suffers, agonizes, thrashes about in his conscience, and only after much doubt succumbs. Iago never doubts as he inexorably drives his victim into perdition. Hence at the complexity of Othello’s persona Iago indeed pales by comparison.

Othello provides the student with the opportunity to the rationale for marriage: “she loved because of ……….”” Is this sufficient? What is it that leads our married couples to early on seek separation, a denouement that afflicts over 50% of marriages? Othello’s love for Desdemona is romantic love, a rarity in his time and in the upper echelons of Venetian society, where marriage was first and foremost a business transaction. Is romantic love a maladaptive evolutionary trait? Indeed, murder-suicides are all too frequent among couples in contemporary Puerto Rican society and spousal abuse is a fast growing plague. Othello provides a unique opportunity for the student to address these cardinal issues so prevalent in our contemporary society. And let us not to forget the pervasive undercurrent of racial prejudice that launches the play.

KING LEAR

KEY ISSUES: Aging, Blindness, Communication, Dementia, Depression, Family Relationships, Father-Daughter Relationship, Father-Son Relationship, Grief, Love, Mental Illness, Nature, Obsession, Parenthood, Power Relations, Rebellion, Suffering,

King Lear, with its themes of family, loyalty, madness, and community is rich with ideas to pursue with which students will readily identify, particularly in this age of heightened awareness about domestic violence and the reality of an growing aged population. When reading King Lear, it is helpful to understand the Elizabethan “Great Chain of Being[62]” (scala naturae)[63] in which nature is viewed as order and, as Rosenblatt (1984) states, “that there was a belief in an established hierarchy within the universe.”[64] In this world everything had its own relative position beginning with Heaven, the Divine Being, and the stars and planets which are all above. On earth the king is next, then the nobles on down to the peasantry. Holding the lowest position were the beggars and lunatics and finally, the animals. Interrupting this order is unnatural. King Lear’s sin was that he disrupted this chain of being by relinquishing his throne; his action has profound cosmic implications. By allowing his daughters and their husbands to rule the kingdom, the natural order of things was profoundly disturbed. His notion that he still is in control despite having divided the kingdom is a delusion. According to Elizabethan philosophy this sets in motion the tragedy and causes the misfortunes that occur later as the play unfolds: when the unnatural occurs, chaos rules.

Lear descends into madness upon the division of his kingdom between his two vile, elder daughters. At a particular instant in this tragedy, Lear is trapped outside in the midst of a terrible storm[65] during which, his insanity becomes evident and inescapable. We must not neglect that he is amidst a storm and thus cold and wet, (as Lear states as he notes his own madness). These characteristics of “wet” and “moist” are direct causes, in addition to other factors, of Lear’s insanity. These are symptoms of an excess of pituita, or fleagme. This mental states result from, according to Burton[66], an “over-moiste braine”, which causes a form of insanity called dotage. Likewise, Lear’s very age puts him at risk for such an outcome. “Distemperance, caused by old age, which being cold and dry, and of the same quality as melancholy is, must needes cause it, by dimunition of the spirits and substance, and increasing of adust humours” (Burton, p. 164). From the start of the play, it is obvious Lear is old, this being the reason for the division of his kingdom; he is old and tired. Lear’s disrupted homeostasis of his humors, mixed with his old age that would naturally result in an excess of “black bile” resulted in his disturbed mental state and leads to his eventual yet untimely death. “Our intemperance it is, that pulls so many several incurable diseases upon our heads, that hastens old age, perverts our temperature, and brings upon us sudden death.” (Burton, p.128).

But it is his unnatural relinquishing of the inescapable duties of kingship what brings about Lear’s downfall and which ultimately leads to his death: the abrupt surrender of his life in the final scene with its unfathomable forlornness attests to this: “Pray you, undo this button. Thank you, sir. Do you see this? Look on her! Look, her lips. Look there, look there. [Lear dies].” In my opinion Shakespeare has given us here the most poignant of death scenes; even overshadowing Capulet’s coming to grips with Juliet’s presumed death as he states: “Death lies on her like an untimely frost. /Upon the sweetest flower of all the field.”(Romeo and Juliet IV, 5). Framing this play with the reality of the solitude and accompanying depression of old age, and its attendant loss of the fortitude of the past, makes it possible for the student to experience how tragic aging can be for a patient deprived of his autonomy.

HAMLET

KEY ISSUES: Death and Dying, Dementia, Depression, Family Relationships, Father-Daughter Relationship, Grief, History of Medicine, Homicide, Incest, Love, Mental Illness, Mother-Son Relationship, Mourning, Power Relations, Religion, Sexuality, Suicide,

At the outset it must be made diaphanously clear that we are here face-to-face with one of humanities most enduring treasures: far more than a mere medical treatise on melancholy. But there are undercurrents in the play that have medical relevance in several ways, though it is important not to reduce the play’s remarkable complexity by overemphasizing or straining the clinical connections one can draw from it. The play raises questions about evidence and action: at what point does one have enough information to be sure that one’s action is going to be the right one (both effectively and ethically)? Hamlet doubts the identity and motives of the ghost, and has the murder reenacted in a play which functions as a kind of experiment, trying to prove Claudius’s guilt by exposing his unconscious reaction (a reaction mediated by the autonomic system and hence beyond Claudius’s control)[67]. Even after this, though, Hamlet cannot find within him the strength of will to carry out the act of avenging his father’s death: therefore his recurrent hesitancy: a death never avenged.

But there is another element not often addressed: Hamlet’s youth. Because of the role’s overwhelming technical and artistic demands the character requires a mature actor. But Hamlet is actually an adolescent or at most a very young man[68]. Renaissance education, such as the one provided at Wittenberg, where Hamlet was studying, ended about age 20.[69] So Hamlet is about the age of the students at entry into advanced studies, so if properly handled they can be induced to relate to him, and perhaps relate far more closely than an older person who only sees the philosophical and dramatic aspects of the play. It is my opinion that for a young person, relating to Hamlet or Ophelia (as they would to the even younger Romeo and Juliet) shall prove a unique, albeit taxing entry, into the conundrum that youth represents and that Shakespeare depicts.

Hamlet’s evident youth could have led to his uncle Claudius being preferred to ascend to the crown following the king’s death. His youth makes him ill prepared emotionally to cope with the strains brought upon him by the unfolding tragedy. This cracks his stability and renders him impotent to act against his uncle, and yet he thrashes about causing death and mayhem. Were we to view Hamlet in the context of the “tragic hero” his “tragic flaw” is not some pathologic hesitancy, but the indecisiveness inherent to youth, much as Lear’s “tragic flaw” would then be old age. Shakespeare follows somewhat the Aristotelian theory of tragedy and theater. However it is not part of the project to enter into literary critique. It is not often that students are confronted with viewing the two extremes of life as defects. To be alive in a swirling world is flaw enough.

Hamlet’s ethical struggle leads him to consider, in minute and eloquent detail, what it means to be human, embodied, and mortal. He contemplates suicide and wrestles with his fear of a possible afterlife, but the solidity of the dead Polonius and the “anatomy lesson” given to him by the gravedigger present him with a more materialist view of being human: Yorick’s hollow and silent skull seems to lead him to a fatalistic–and one might say secular and modern–attitude to action and to death. Rather than pursuing vengeance, he seems to forget the ghost and allows Claudius’s own machinations to bring about the chain of deaths that end the tragedy. In the end he kills Claudius not because he killed his father, but because he killed his mother. The Freudian overtones ring clearly.

In a reenactment of the biblical Cain and Abel story, Claudius kills his brother, Hamlet’s father, with the twist that Claudius not only murdered his brother but married his sister-in-law. Echoing Genesis and Sophocles, Hamlet is haunted by his father who in spirit at least, or as a phantasm fruit of his imaginings, refuses to die. And for their human transgressions Gertrude and Ophelia, are, in a sense, cast out of Eden. The point is obvious; universal Hamlet is, and we all have had to survive the passage in our lives akin to his: we can all remember when we too asked the most important existential question: To be or not to be? And doubtless that we all have had to, and as teachers, we must remember our own weaknesses if we are to impact our students. We too felt the blood passion that arises from the desire to succeed at any price. In confronting Hamlet at about his same age the student can be enriched by self-examination. Students are to grapple with the complexities of these issues, but then, to grapple with Hamlet is to grapple with life

CONCLUSION

These four plays have medical overtones, but the dominant theme is not medical and the objective is far from establishing a diagnosis. These are tragedies, and as Nietzsche stated in The Birth of Tragedy, “I fear that, with our current veneration for the natural and the real, we have arrived at the opposite pole to all idealism, and have landed in the region of the waxworks.” Thus this course is not directed at attempting to establish a medical causality for the characters’ actions and outcomes. If that were the motive force of each play they would be misfortunes, not tragedies. Shakespeare did not write misfortunes, but tragedies.

The ultimate objective is to acquaint the interested student with the magic of Shakespeare’s ineffable imagination and his searing and trenchant analyses of humanity: its splendor as well as its failings as depicted via paradigmatic characters. Finally, the relationship to evolutionary theory is inescapable for, as that formidable evolutionist Theodosius Dobzhansky so trenchantly stated: “nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution”. What moves the characters to act as they do? What are their deep motivations? Why against all “logic” do they self-destruct, as many do in our day and age (though not with such loftiness)? What is it they give way to? Such an appreciation of nature’s (and thus humanity’s) primum mobile, harks back to the immortal last sentence of the first edition of Darwin’s monumental “Origin of Species”: an oeuvre as enduring as Shakespeare’s:

“There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

What boundless optimism! And so in Shakespeare! For his paradigmatic creations mutate and transform themselves into each and all of us, and are undeniably the emblems of our own individual condition.

TEACHING STRATEGIES:

Critical assessment of the written plays as well as complete theatrical representations.

ASSESSMENT STRATEGIES: Students will be required to attend and view the corresponding act of each play, read the assigned text and be prepared to discuss with faculty the issues raised by the theatrical presentation and the reading. Emphasis will be placed on the human context of and how it can be applied to the physician-patient relation.

GRADING SYSTEM: Letter grade :A-F

RESOURCES:

Text Resources:

- Text of Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello and King Lear will be provided before each session

- Audiovisual Resource: Copies of theatrical representations of the four plays will be provided in DVD format.

GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS AND COURSE REQUIREMENTS:

Students with a health condition or situation that, according to the law, makes them eligible for reasonable accommodation have the right to submit a written application to the professor and the Dean of their Faculty, according to the procedures established in the document, Submittal Process for Reasonable Accommodation of the Medical Sciences Campus. A free copy of this document may be obtained at the Office of the Dean for Student Affairs, second floor of the School of Medicine Pharmacy building. A copy may also be obtained at the Office of the faculty Deans as well as in the MSC web page. The application does not exempt students from complying with the academic requirements pertaining to the programs of the Medical Sciences Campus.

- It is a REQUIREMENT to participate and be punctual to all activities. If you will not be able to attend due to a mayor cause (sickness, death in the family, etc.) you are responsible of notifying the course coordinator PRIOR to the activity and to make arrangements for reposition of the missed activity. As a general rule, no excuses will be given unless there is an emergency and each case will be evaluated separately. If you are absent, you MUST present a formal excuse from the Office of the Assistant Dean of Student Affairs of the appropriate faculty prior to the completion of the course.

- In case there is a special need to be absent, the procedures of the “Politica Institucional para Excusar Estudiantes de Actividades Evaluativas o Docentes” will be followed.

- Students are expected to demonstrate each and every one of the course objectives.

- Should knowledge become available that dishonesty regarding any particular examination has occurred; the course faculty reserves the right to cancel the examination before or after it has been administered and to require a repeat exam or completely eliminate the exam from the course evaluation.

- Dress code: All students must comply with the UPR School of Medicine Dress code, approved in 1996 and revised in 2007. (Posted at the SOM Web Page)

Ángel A Román-Franco MD

[1] Life expectancy at birth was only about 48 years, although anyone who made it through the first 30 years was likely to live for another 30. Life expectancy varied from place to place–it was particularly low in cities where crowded conditions and poor sanitation increased the dangers of disease: see Singman JL: Daily Life in Elizabethan England ; The Greenwood Press “Daily Life Through History” Series; Greenwood Press; Westport, Connecticut • London; 1995

[2] Peterson, Kaara L. “Historica Passio : Early Modern Medicine, King Lear, and Editorial Practice”

Shakespeare Quarterly – Volume 57, Number 1, Spring 2006, pp. 1-22

[3] Well known is Paracelsus’s opposition to Galenic medicine, so their joint mention must have had resonances among the theater-going public at the outset of the 15th century ( See: Philip Ball THE DEVIL’S DOCTOR: Paracelsus and the World of Renaissance Magic and Science. Heinemann/Farrar/Straus/Giroux 2006, 448pp)

[4] Rossi, Arcangelo “L’Art et la science au temps de William Shakespeare: Des chiffres et des lettres.” RLM nos. 1431-1436 (1999): 19-41.

[5] Cosman BC. All’s Well That Ends Well: Shakespeare’s treatment of anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998 Jul;41(7):914-24.

[6] Plato is fond of using the physician as his model of the rational ruler, and in The Republic he explicitly considers the question of whose agent the physician is. Early in that dialogue he offers us this exchange between Socrates and Thrasymachus:

Now tell me about the physician in that strict sense you spoke of: is it his business to earn money or to treat his patients? Remember, I mean your physician who is worthy of the name?

To treat his patients.

For a detailed discussion of the topic see: Osler, William: Physic and physicians as depicted in Plato in Osler W. Aequanimitas with other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses, and Practitioners of Medicine. London. HK Lewis and Co Ltd 1948. (Reprinted by The Classics of Medicine Library, Division of Gryphon Editions Ltd., Birmingham, Alabama 1978).

[7] King Lear and Macbeth were both published on the same year as Cervantes’s Don Quijote

[8] Cervantes and. the magicians. Great Britain, The Mayflower Press,. 1934

[9] Esbozos y rasguños: el cervantismo, en Obras Completas, Madrid, Aguilar, 1943.

[10] Discurso sobre el Quijote y las diferentes maneras de comentarle y juzgarle, Madrid, Imprenta de Manuel Galiano, 1864.

[11]Esbozos y rasguños: el cervantismo, en Obras Completas, Madrid, Aguilar, 1943.

[12] Idearium español, ed. E. Imman Fox, Madrid, Espasa-Calpe, 1990.

[13] “Ante las fiestas del Quijote,” Alma española, 13 de diciembre de 1903; y “Don Quijote en Barcelona,” Alma española, 20 de diciembre, 1903

[14] “Psicología de don Quijote y el quijotismo,” en Obras completas, Madrid, Aguilar, 1947

[15] El problema nacional, ed. Andrés de Blas, Madrid, Biblioteca Nueva, 1996

[16] España tal y como es, ed. Antoni Jutglar, Barcelona, Anthropos, 1983.

11 Los males de la patria y la futura revolución española, ed. J. Flores Arroyuelo, Madrid, Fundación Banco Exterior, 1990

12 Los problemas del día, Madrid, Victoriano Suárez, 1900.

13 de Unamuno, M.: Vida de don Quijote y Sancho: Obras completas, IV, Madrid, Afrodisio Aguado, 1950, pp. 93-393.

[20] Harwood A. The hot-cold theory of disease. Implications for treatment of Puerto Rican patients. JAMA. 1971 May 17;216(7):1153-8.; Galli N.The influence of cultural heritage on the health status of Puerto Ricans. J Sch Health. 1975 Jan;45(1):10-6

[21] Foster, GM. Hippocrates’ Latin American Legacy: Humoral Medicine in the New World. Gordon and Breach. 1994.

[22] Reichel-Dolmatoff, G. 1968. Amazonian Cosmos. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 111

[23] Ahern, E. 1975. Sacred and Secular Medicine in a Taiwan Village: A Study of Cosmological Disorders. In: National Institutes of Health (NIH), Medicine in Chinese Culture, pp. 91-113. US Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

[24] Colson. A. B. 1976. Binary Oppositions and the Treatment of Sickness among Akawaif. In: J. Louden, ea., Social Anthropology and Medicine. Academic Press. New York.

[25] Beck, B. 1969. Colour and Heat in South Indian Ritual. Man, 4: 553-572.

19 Messer, EA 1981. Hot-Cold Classifications: Theoretical and Practical Implications of a Mexican Study. Soc. Sci. Med., 15B: 133-14

20 HIPPOCRATE. Opera omnia (texte grec) Venise : Alde, 1526

21 Eliade, Mercia: Le Chamanisme et les techniques archaiques de l’extase, Librairie Payot, Paris, 1951.

[29] fl. 3d cent. BCE,. School of medicine in Alexandria, influential until the 4th cent. AD He considered plethora (hyperemia) as the primary cause of disease; suggested that air carried from the lungs to the heart is converted into a vital spirit distributed by the arteries. Developed a reverse theory of circulation (veins to arteries). Studying from dissections observed the convolutions of the brain; named the trachea, and distinguished (as did his contemporary Herophilus) between motor and sensory nerves. He also devised a catheter and a calorimeter.

[30] fl. 3rd BCE, Member of the Alexandrian School of Medicine and father of scientific anatomy. Coeval with Erasistratus at Alexandria (v.s.) Held public dissections contrasting human and animal morphology; studied the brain’s structure (recognized it as site of intelligence); spinal cord (characterized motor and sensory nerves); anatomized the eye, digestive tube (named the duodenum), reproductive organs, and the circulatory system.

[31] Currier, RL. The Hot-Cold Syndrome and Symbolic Balance in Mexican and Spanish-American Folk Medicine. Ethnology 5:251-263. 1966.

[32] Laurentius, Andreas. A Discourse of the Preservation of Sight: of Melancholike Diseases: of Rheumes and of Old Age (1599). London: Oxford University Press. 1938.

[33]. Peccant is one of those rarely used but apt words. The behaviors — overeating, underexercising, an unhealthy diet — that underlie so much disease today are peccant behaviors. “…the subtile parts of the tobacco in inspiration are carried into the trachea and lungs, where they loosen the peccant humours adhering thereto, and promote expectoration.” (From the entry to tobacco in the First Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, 1771). The word peccant comes from the Latin peccans, from peccare (to sin, to commit a fault, to stumble- and hence our pecado). Peccant involves stumbling of a sort — falling into unhealthy behavior.

[34] Cupping, an ancient Chinese method of causing local congestion is performed by creating a partial vacuum in cups placed on the skin either by means of heat or suction. This draws up the underlying tissues, blood stasis is formed and localized healing takes place.

[35] According to Suetonius and Plutarch, sometime in March when Caesar was making sacrifices, a soothsayer or astrologer named Spurinna warned Caesar of danger on a date no later than the Ides of March.

[36] MAGNETIC THERAPY LTD, Ellesmere Centre Walkden – Worsley, Manchester, M28 3ZH, United Kingdom.

[37] Pott, P.: Chirurgical Observations relative to the Cataract, the polypus of the nose, the cancer of the scrotum, … ruptures, and the mortification of the toes, etc (London, 1775)

[38] Cinchona calisaya Wedd

[39] The Jesuits brought the bark of this plant with them to Rome (Father Bartolomé Tafur) and Spain (Father Alonso Messias Venegas). The first load of bark was sent to Europe in 1641, to Seville, the only port which could then accept goods from the New World. In Rome the effect of the bark was tested under the supervision of Cardinal Juan de Lugo and Gabriella Fonseca, the personal physician to Pope Innocent X. In 1654 the Peruvian bark was introduced into England, but the British protestants objected to testing a “Catholic potion”.

[40] Alexander von Humboldt :”It almost goes without saying that among Protestant physicians hatred of the Jesuits and religious intolerance lie at the bottom of the long conflict over the good or harm effected by Peruvian Bark.”

[41] William Leigh, Great Britaines Great Deliverance from the Great Danger of Popish Powder (London 1606

[42] Allium cepa (LINN.): Antiseptic, diuretic. A roasted Onion is a useful application to tumours or earache. The juice made into a syrup is good for colds and coughs. Hollands gin, in which Onions have been macerated, is given as a cure for gravel and dropsy. Ambroise Pare propounded the treatment of wounds with onion slices: Paré, A (1575). Les oeuvres de M. Ambroise Paré conseiller, et premier chirurgien du Roy avec les figures & portraicts tant de l’Anatomie que des instruments de Chirurgie, & de plusieurs Monstres. ……. Paris: Gabriel Buon.

[43] In fact Capt. Cook believed otherwise. In a paper delivered to the Royal Society he said of malt, ‘This is without doubt one of the best antiscorbutic sea-medicines yet found out; and if given in time will, with proper attention to other things, I am persuaded, prevent the scurvy from making any great progress for a considerable time’. (see: [COOK, Captain James] PRINGLE, Sir John, editor. A Discourse upon some late improvements of the Means for Preserving the Health of Mariners. Delivered at the Anniversary Meeting of the Royal Society, November 30, 1776. By Sir John Pringle, Baronet, President. Published by their Order.

[44] DICTIONARY OF SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHY, Vol. IV: 37-38. © 1980 American Council of Learned Societies.

[45] 1511saw the Physicians and Surgeons Act limiting medical practice to those who had been examined. Oxford and Cambridge universities retained their rights to issue licences to practice. In 1522 An Act set out “The Privileges and Authority of Physicians in London” (In 1518 the Royal College of Physicians of London was founded to oversee the practice of medicine within a seven mile radius of the City by licensing recognised physicians).

[46] Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto: Heauton timoroumenos (act I, sc. 1)

[47] DESCARTES, René Discours de la Methode pour bien conduire sa raison, & chercher la verité dans les Sciences. Plus La Dioptrique, les Meteores, la Mechanique, et la Musique, Qui sont des essais de cette Methode… Paris, Angot 1668.

[48] Scienza nuova (1725); The First New Science, edited and translated by Leon Pompa. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

[49] K. Jaspers, The Great Philosophers 3, New York etc. 1993

[50] English translation of mens sana in corpore sano a phrase coined by the satiric poet Decimus Iunius Iuvenalis, otherwise known as Juvenal (Satire X line 356).

[51] The word tragedy literally means “goat song,” probably referring to the practice of giving a goat as a sacrifice or a prize at the religious festivals in honor of the god Dionysus.

[52] Macbeth III,4

[53] Norton SA, Paris RM, Wonderlich KJ. “Strange things I have in head”: evidence of prion disease in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Jan 15;42(2):299-302.

[54] Physicians

[55] As an aside, it should be noted that Shakespeare does not appear to have been disdainful of coeval medical discoveries. For example, it has been suggested that Eustachius’ discovery of the connection between the middle ear and the pharynx later inspired Shakespeare to write his play Hamlet – whose father was killed by poison poured into his ear. Another explanation for the possibility of a murder via auris, which was known to occur in 16th century Italy, is based on the knowledge of that time about absorption of some substances from the ear.

[56] The Dawn: Thoughts on the prejudices of morality. Selections (from 2d edition, pub. 1887)

[57] Othello syndrome (conjugal paranoia): A psychosis in which the content of delusions is predominantly jealousy (infidelity) involving spouse. It is a form of delusional paranoia in which the patients possess the fixed belief that their spouse or partner has been unfaithful. Often, patients collect bits of evidence (the handkerchief) and attempt to restrict their partner’s activities, its ultimate expression being murder.

[58] Turnbull, William. Othello: A Critical Study. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1892.

[59] John Milton : Paradise Lost. Book i. Line 261.

[60] Coleridge ST: (Lectures 1808-1819 On Literature 2: 315)

[61] Translation by Jonathan H. Ward (ilbasso@aol.com)

[62] Fray Diego de Valades: Rhetorica Cristiana, Perugia 1579; Arthur O. Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936, Harper & Row, 1960.

[63] Aristotle introduced the idea of the scala natura – the ladder of nature – according to which the natural world is interpreted in terms of the principle of plenitude, the overflowing abundance of the first principle or Godhead which creates successive beings. The further the beings are from the source the more ontologically impoverished they are.

[64] William Shakespeare: King Lear (Barron’s Book Notes), Arthur S. Rosenblatt (Editor) October 1984

[65] As an interesting aside, please note Lear’s challenge to nature in the scene on the heath (III, 2):

Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! rage! blow!

You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout

It is interesting that King Lear was written ca. 1603, barely a century after Columbus’ epic, and a Taino word is already enough familiar Elizabethan verbal currency to be used on the stage.

[66]Burton, Robert. The Anatomy of Melancholy, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989.

[67] Psychophysiological detection of deception or guilt from Matte, James A: Forensic Psychophysiology Using The Polygraph: Scientific Truth Verification – Lie Detection. J.A.M. Publications., Williamsville, NY. (1998) 800pp

[68] Hamlet is often referred to as ‘young’. See I.i.174-175, I.iii.5- 14 and 115-126, I.v.16 and 38, II.ii.131-132 and 189-190, III.i.154 and 161, IV.i.19, IV.vii.70-81…96-104.

[69] Robert F. Seybolt. The Manuale Scholarium: An Original Account of Life in the Medieval University. Harvard University Press, 1921; Renaissance Student Life: The Paedologia of Petrus Moselanus. Univ. of Illinois Press, 1927; Seybolt, Robert Francis, trans. The Manuale Scholarium: An Original Account of Life in the Mediaeval University. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1921.