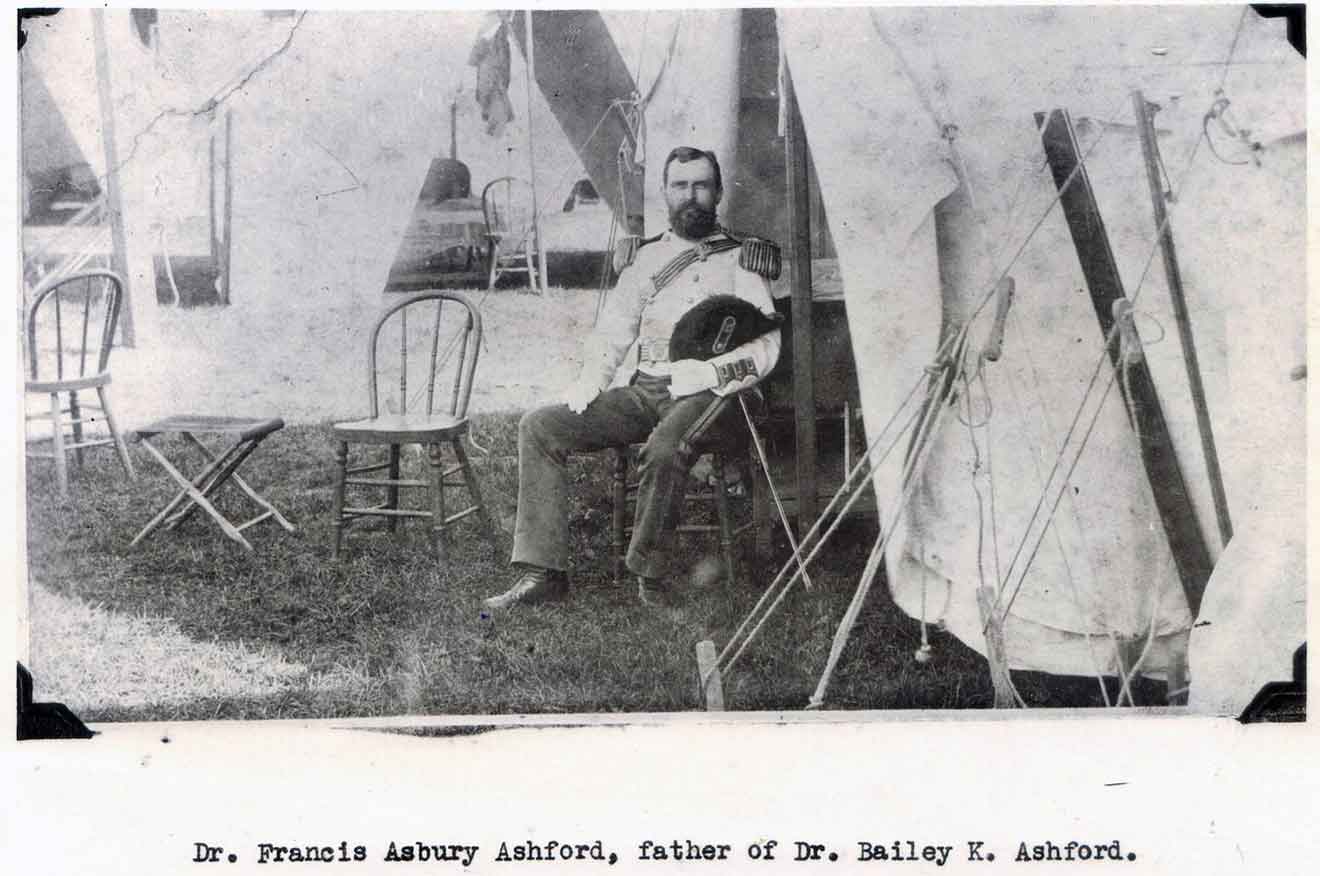

Dr. Bailey K. Ashford was born on September 18, 1873, in Washington, D.C. His father was Dr. Francis Asbury Ashford, and his mother was Mrs. Isabella Walker Kelly. Ashford’s father died in 1883 when he was barely ten years old.

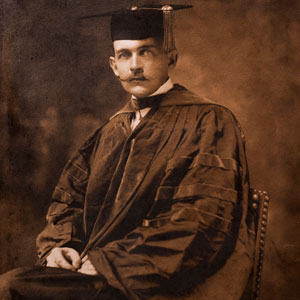

He studies in his hometown, graduating as a doctor at Georgetown University in 1896. The following year he entered the US Army of his country as a medical officer, being called upon to achieve, through successive promotions, the rank of colonel. Colonel Ashford participated in the Spanish American War of 1898 and came to Puerto Rico as part of the expeditionary troops of General Miles. When the military occupation of the Island was formalized and the government of the territory was integrated, he was ordered to remain in Puerto Rico, where his studies and experiences in Tropical Medicine can be very useful.

Dr. Ashford became closely bound to the island, immediately after his arrival in 1898 during the Spanish-American War. After the occupation forces landed on Guanica, Ashford went to Ponce and later to Mayagüez. While in Mayagüez, he reported to the War Department stated that the country people were “a pale, dropsical, unhealthy-looking class, evidently suffering from lack of meat, although there must be something else, not yet understood.” In 1899, he had married Maria Asunción López Nussa, daughter of a prominent Mayagüez family. Her father Ramon B. López was regarded as something of a radical then. In starting the first daily newspaper (La Correspondencia de Puerto Rico), López shaped much of public opinion on the Island. His wife Doña Micaela Nussa y Pascual from a noble family of Barcelona was the model of social propriety.[3] Later that year, he was ordered to command the General Hospital in Ponce.

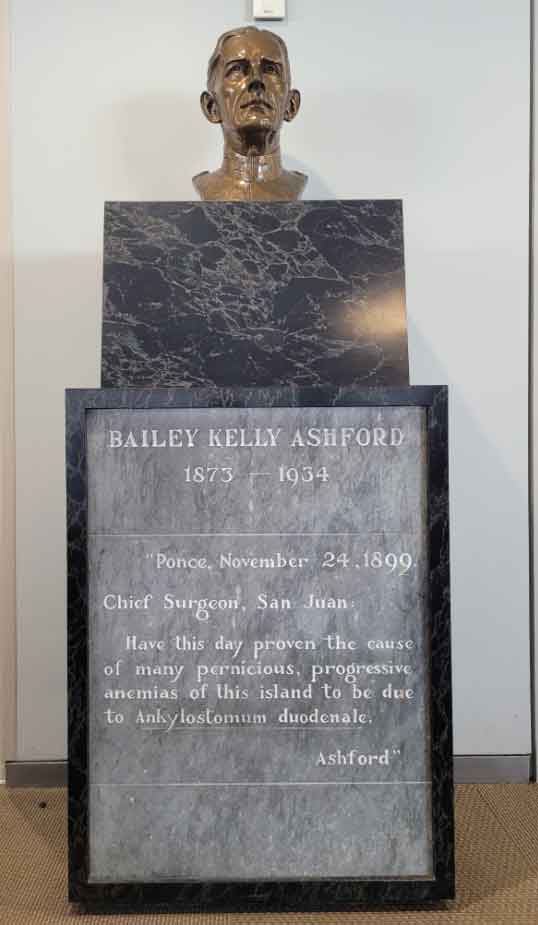

Shortly after taking command of the hospital, the island of Puerto Rico was devastated by Hurricane San Ciriaco. As a result of this event, Ashford opens a hospital in Ponce to attend to civilians and notices paleness, edema, and anemia among his patients. While Ashford was examining their patients’ blood, he encountered a marked increase in eosinophils, which reached as much as 40 percent. Remembering that eosinophilia was common in certain worm diseases, he examined the feces of these patients and encountered oval objects with four fluffy gray halls inside. He examined Manson’s textbook, “Tropical Diseases,” and he found a photograph of a similar egg labeled Ancylostoma duodenale described by anemic Italians who worked in the St. Gothard tunnel in Switzerland. The following telegram, which is engraved on the base of the bust of Ashford located today inside the Conrado F. Asenjo Library in the Medical Science Campus of the University of Puerto Rico announced his discovery: “Ponce, November 24, 1899 – Chief Surgeon, San Juan – Have this day proven the cause of many pernicious, progressive anemias of this Island to be due to Ancylostoma duodenale – Ashford..” Document No. 808, published in 1900 by the Sixty-first Congress of the United States, contains his masterly description of the clinical aspects of the disease and remains as a medical classic.

Ashford assumed the risk of treating patients with the toxic drug thymol and recovered the adult hookworms from the stools. Ashford knew that thymol was capable of act like a poison, and in his own words: “And it took a considerable amount of nerve, to say the least even to apply the remedy which was our only hope, and which expelled the worm.” Subsequently, it was proven that the hookworm in Puerto Rico and the Western Hemisphere was a distinct species. Ashford was joined by a young Public Health Service physician, Dr. Walter W. King, and together they treated at least 100 cases of hookworm anemia in the Tricoche Hospital. Soon he and his assistant, Dr. King, recognized anemia, described as laziness and indolence, as a disease.

As a result of Ashford’s work the Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico authorized the Governor to adopt measures leading to the study and cure of tropical anemia on the Island. The War Department named Dr. Bailey K. Ashford, the United States Public Health Service assigned Dr. Walter W. King and the Insular service provided Dr. Pedro Gutiérrez Igaravídez, Medical Director of the Bayamón Hospital, to a board called the Anemia Commission of Puerto Rico. [9] The Anemia Commission installed a small hospital in Bayamón where hundreds of sick victims of anemia attended every day. For Ashford and King, local resources were insufficient, and tents were set up to accommodate a larger number of patients. These were brought to Bayamón in hammocks or stretchers carried by family or friends, mostly jibaros from all over the island.

The hard work of Doctors Ashford and King was finally recognized and in 1904 the government of Puerto Rico promoted a campaign to extend the campaign against anemia, which makes three dozen doctors based in different populations participate in this effort. In this way, the obtaining of even more satisfactory results was made possible to the point that the scientific achievements achieved will serve for the development in the United States of a similar program.

Ashford’s methods, which found worldwide recognition, blazed the trail for the work of the Rockefeller Commission in 1909 to stamp out hookworm in infested areas of the southern United States. This Commission led to the formation of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1913, which later formed the International Health Board in 1916, and, finally, the international Health Division in 1927, thus restoring to useful and healthful lives millions of disease-ridden individuals in all areas of the world.

It has been shown that anemia treated in time could be curable. While Ashford was for a short time in Washington in 1906, he maintained his interest in continuing a group of men trained for action. And have the idea of an Institute of Tropical Medicine and Hygienic in Puerto Rico. He wrote a letter, addressed to the Governor of Puerto Rico, Beekman Winthrop, to create a School of Tropical Medicine, under the auspices of some great United States University.

The importance of the discovery and subsequent treatment of anemia in Puerto Rican peasants was that it defeated the belief of the time that anemia in rural areas was caused by hunger, dirt, and racial degeneration. At the beginning of the 20th century, the diagnosis, cause, and treatment of anemias were the subject of heated discussions in those years. For years, Ashford had to resist criticism from skeptics, because the anemia he described was much more severe than in other countries and the proportion infected with hookworm was also huge.[ Ashford’s success in treating anemia was also reflected in the economic sphere of the island. By 1900, according to sources supplied by farmers to the Puerto Rico Ilustrado magazine, seventy-five percent of workers suffered from anemia. A decade later, only 15 to 20 percent suffered from anemia. As a result of this decline, and with the idea that, with stronger and fitter workers, this resulted in benefits not only for the workers but also for the owners of farmland. As of the date of the report, it was reported that more than 300,000 people had already been successfully treated for anemia.

The success of his medical treatment made him seem capable of working miracles. In “Bailey K. Ashford, Mas Allá de Sus Memorias” (Bailey K. Ashford, Beyond His Memories), we find the following note from a jibaro asking him to return to the rural area: “Por el camposanto están diciendo que le mande a decir que vengan pronto para que Ustedes le den vida como se la ha dado a los otros que han curado” (By the cemetery they are saying to send him to tell him to come soon so that you can give him life as he has given it to the others who have healed).

Ashford also found that most cases of endemic anemia suffered by Puerto Ricans were due to intestinal parasites. In 1910, Ashford figured in the list of those recommended for the Nobel Prize. And by 1911, due to his aggressive and effective campaign against anemia, Ashford reached an enormous prestige. When the Department of Health was established that very same year, Ashford was offered the position of Head (or Director) of the new department. However, he did not accept the appointment due to his belief that a civilian position was incompatible. In 1911 he founded, together with doctors Pedro Gutiérrez Igaravídez and Isaac González Martínez, the Institute of Tropical Medicine that later would become the School of Medicine of the University of Puerto Rico.

The Institute of Tropical Medicine had three main activities: teaching, including the training of sanitary officials and inspectors; fieldwork in the mountainous districts of the country and clinical and laboratory research on infectious diseases. For many years the Institute of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene invited universities in North America to join them in the establishment of an American School of Tropical Medicine. Finally, during the summer of 1923 arrangements were concluded with Columbia University providing that they should furnish and pay the salaries of a Director of the School and three Professors. The Island was to pav the rest and to build a new building. This was completed and inaugurated on September 22, 1926, and was modeled after the Monterrey Palace of Salamanca, Spain, and was situated on Ponce de León Avenue, just east of the capital overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. Over the next twenty years, the School of Tropical Medicine grew into an institution whose achievements were acclaimed throughout the world. A research hospital was added, and the laboratory facilities greatly expanded.

Ashford’s achievements in Puerto Rico were recognized worldwide. In World War I his concept of bringing care closer to the patient was instituted on the battlefront in Europe, with Dr. Ashford in charge of training medical personnel. He visited Brazil and Cuba to provide advice and in Egypt, he was distinguished for his contribution to medicine.

His participation in World War I earned him decorations from the US and British governments. Other distinctions he received include his election as president of the Puerto Rico Medical Association and his exaltation to the presidency of the American Society of Tropical Medicine. He also received honorary degrees from the Universities of Puerto Rico and Columbia. He published in the journal of the American Medical Association and in other various scientific publications works in which he related his research and gave an account of the results obtained. On March 26, 1934, he presented to the V Pan American Medical Congress, which was held in San Juan, a monograph entitled Some modalities of sprue in Puerto Rico, written in collaboration with Dr. Ramón Suárez, which aroused great interest and was widely commented on.

Ashford demonstrated as Dr. Rigau Pérez mentions very well, that the scientific research directed at the problems of the Puerto Rican reality was exemplary, due to its quality, and of local and international benefit. He managed to reduce mortality in the poorest of the peasant population. He reached that goal both through his scientific pursuit and through his personal efforts to get the government to allocate funds for anemia research. And, above all, for his determination to bring the benefits of his discoveries to where they are most needed.

On August 1 of the same year, on the publication of his autobiographical book A Soldier in Science, the Puerto Rico Medical Association organized an evening in his honor. Dr. Ashford passed away on November 1, 1934.

*Casa Dr. Bailey K. Ashford,

National Register Database and Research

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/database-research.htm

The biography of Dr. Bailey K. Ashford is an excerpt from the nomination document submitted by Prof. Daniel Mora Ortiz (daniel.mora2@upr.edu) for the inclusion of Dr. Ashford’s house in the National Register of Historic Places.

This work was carried out for the State Historic Preservation Office (SHIPO) of San Juan, Puerto Rico.